Andy Warhol Foundation for Visual Arts, Inc. v. Goldsmith, 598 U.S. ___ (2023)

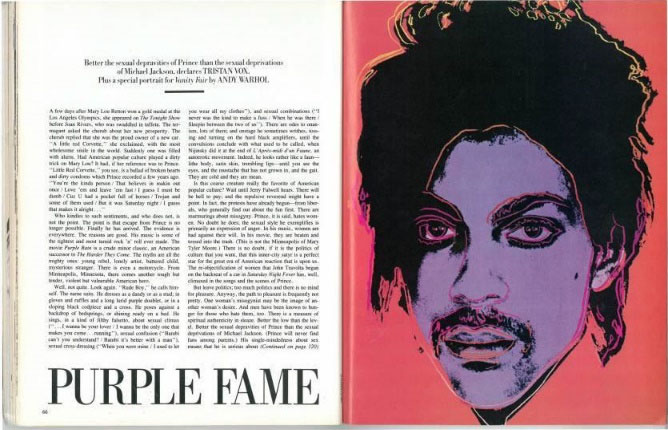

In 1984, Goldsmith, a portrait artist, granted Vanity Fair a one-time license to use a Prince photograph to illustrate a story about the musician. Vanity Fair hired Andy Warhol, who made a silkscreen using Goldsmith’s photo. Vanity Fair published the resulting image, crediting Goldsmith for the “source photograph,” and paying her $400. Warhol used Goldsmith’s photograph to derive 15 additional works. In 2016, the Andy Warhol Foundation (AWF) licensed one of those works, “Orange Prince,” to Condé Nast to illustrate a magazine story about Prince. AWF received $10,000. Goldsmith received nothing. When Goldsmith asserted copyright infringement, AWF sued her. The district court granted AWF summary judgment on its assertion of “fair use,” 17 U.S.C. 107. The Second Circuit reversed.

The Supreme Court affirmed, agreeing that the first fair use factor, “the purpose and character of the use, including whether such use is of a commercial nature or is for nonprofit educational purposes,” weighs against AWF’s commercial licensing to Condé Nast. Both the 1984 and the 2016 publications are portraits of Prince used in magazines to illustrate stories about Prince; the “environment[s]” are not “distinct and different.” The 2016 use also is of a commercial nature.

Orange Prince reasonably can be perceived to portray Prince as iconic, whereas Goldsmith’s portrayal is photorealistic but the purpose of that use is still to illustrate a magazine about Prince. The degree of difference is not enough for the first factor to favor AWF. To hold otherwise would potentially authorize a range of commercial copying of photographs, to be used for purposes that are substantially the same as those of the originals. AWF offers no independent justification for copying the photograph.

Supreme Court rejects a claim of "fair use" arising in a copyright dispute concerning an Andy Warhol silkscreen made from a copyright-protected photograph.

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

Syllabus

ANDY WARHOL FOUNDATION FOR THE VISUAL ARTS, INC. v. GOLDSMITH et al.

certiorari to the united states court of appeals for the second circuit

No. 21–869. Argued October 12, 2022—Decided May 18, 2023

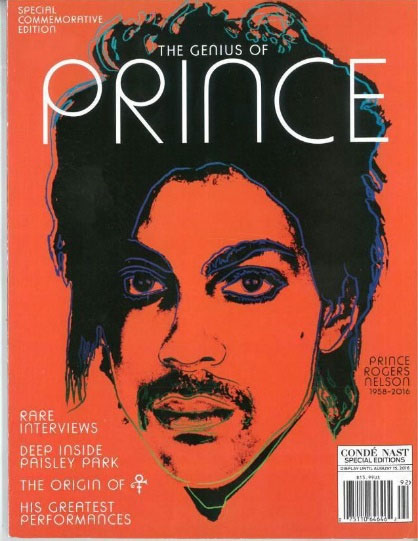

In 2016, petitioner Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. (AWF) licensed to Condé Nast for $10,000 an image of “Orange Prince”—an orange silkscreen portrait of the musician Prince created by pop artist Andy Warhol—to appear on the cover of a magazine commemorating Prince. Orange Prince is one of 16 works now known as the Prince Series that Warhol derived from a copyrighted photograph taken in 1981 by respondent Lynn Goldsmith, a professional photographer. Goldsmith had been commissioned by Newsweek in 1981 to photograph a then “up and coming” musician named Prince Rogers Nelson, after which Newsweek published one of Goldsmith’s photos along with an article about Prince. Years later, Goldsmith granted a limited license to Vanity Fair for use of one of her Prince photos as an “artist reference for an illustration.” The terms of the license included that the use would be for “one time” only. Vanity Fair hired Warhol to create the illustration, and Warhol used Goldsmith’s photo to create a purple silkscreen portrait of Prince, which appeared with an article about Prince in Vanity Fair’s November 1984 issue. The magazine credited Goldsmith for the “source photograph” and paid her $400. After Prince died in 2016, Vanity Fair’s parent company (Condé Nast) asked AWF about reusing the 1984 Vanity Fair image for a special edition magazine that would commemorate Prince. When Condé Nast learned about the other Prince Series images, it opted instead to purchase a license from AWF to publish Orange Prince. Goldsmith did not know about the Prince Series until 2016, when she saw Orange Prince on the cover of Condé Nast’s magazine. Goldsmith notified AWF of her belief that it had infringed her copyright. AWF then sued Goldsmith for a declaratory judgment of noninfringement or, in the alternative, fair use. Goldsmith counterclaimed for infringement. The District Court considered the four fair use factors in 17 U. S. C. §107 and granted AWF summary judgment on its defense of fair use. The Court of Appeals reversed, finding that all four fair use factors favored Goldsmith. In this Court, the sole question presented is whether the first fair use factor, “the purpose and character of the use, including whether such use is of a commercial nature or is for nonprofit educational purposes,” §107(1), weighs in favor of AWF’s recent commercial licensing to Condé Nast.

Held: The “purpose and character” of AWF’s use of Goldsmith’s photograph in commercially licensing Orange Prince to Condé Nast does not favor AWF’s fair use defense to copyright infringement. Pp. 12–38.

(a) AWF contends that the Prince Series works are “transformative,” and that the first fair use factor thus weighs in AWF’s favor, because the works convey a different meaning or message than the photograph. But the first fair use factor instead focuses on whether an allegedly infringing use has a further purpose or different character, which is a matter of degree, and the degree of difference must be weighed against other considerations, like commercialism. Although new expression, meaning, or message may be relevant to whether a copying use has a sufficiently distinct purpose or character, it is not, without more, dispositive of the first factor. Here, the specific use of Goldsmith’s photograph alleged to infringe her copyright is AWF’s licensing of Orange Prince to Condé Nast. As portraits of Prince used to depict Prince in magazine stories about Prince, the original photograph and AWF’s copying use of it share substantially the same purpose. Moreover, AWF’s use is of a commercial nature. Even though Orange Prince adds new expression to Goldsmith’s photograph, in the context of the challenged use, the first fair use factor still favors Goldsmith. Pp. 12–27.

(1) The Copyright Act encourages creativity by granting to the creator of an original work a bundle of rights that includes the rights to reproduce the copyrighted work and to prepare derivative works. 17 U. S. C. §106. Copyright, however, balances the benefits of incentives to create against the costs of restrictions on copying. This balancing act is reflected in the common-law doctrine of fair use, codified in §107, which provides: “[T]he fair use of a copyrighted work, . . . for purposes such as criticism, comment, news reporting, teaching . . . , scholarship, or research, is not an infringement of copyright.” To determine whether a particular use is “fair,” the statute enumerates four factors to be considered. The factors “set forth general principles, the application of which requires judicial balancing, depending upon relevant circumstances.” Google LLC v. Oracle America, Inc., 593 U. S. ___, ___.

The first fair use factor, “the purpose and character of the use, including whether such use is of a commercial nature or is for nonprofit educational purposes,” §107(1), considers the reasons for, and nature of, the copier’s use of an original work. The central question it asks is whether the use “merely supersedes the objects of the original creation . . . (supplanting the original), or instead adds something new, with a further purpose or different character.” Campbell v. Acuff-Rose Music, Inc., 510 U.S. 569, 579 (internal quotation marks and citations omitted). As most copying has some further purpose and many secondary works add something new, the first factor asks “whether and to what extent” the use at issue has a purpose or character different from the original. Ibid. (emphasis added). The larger the difference, the more likely the first factor weighs in favor of fair use. A use that has a further purpose or different character is said to be “transformative,” but that too is a matter of degree. Ibid. To preserve the copyright owner’s right to prepare derivative works, defined in §101 of the Copyright Act to include “any other form in which a work may be recast, transformed, or adapted,” the degree of transformation required to make “transformative” use of an original work must go beyond that required to qualify as a derivative.

The Court’s decision in Campbell is instructive. In holding that parody may be fair use, the Court explained that “parody has an obvious claim to transformative value” because “it can provide social benefit, by shedding light on an earlier work, and, in the process, creating a new one.” 510 U. S., at 579. The use at issue was 2 Live Crew’s copying of Roy Orbison’s song, “Oh, Pretty Woman,” to create a rap derivative, “Pretty Woman.” 2 Live Crew transformed Orbison’s song by adding new lyrics and musical elements, such that “Pretty Woman” had a different message and aesthetic than “Oh, Pretty Woman.” But that did not end the Court’s analysis of the first fair use factor. The Court found it necessary to determine whether 2 Live Crew’s transformation rose to the level of parody, a distinct purpose of commenting on the original or criticizing it. Further distinguishing between parody and satire, the Court explained that “[p]arody needs to mimic an original to make its point, and so has some claim to use the creation of its victim’s (or collective victims’) imagination, whereas satire can stand on its own two feet and so requires justification for the very act of borrowing.” Id., at 580–581. More generally, when “commentary has no critical bearing on the substance or style of the original composition, . . . the claim to fairness in borrowing from another’s work diminishes accordingly (if it does not vanish), and other factors, like the extent of its commerciality, loom larger.” Id., at 580.

Campbell illustrates two important points. First, the fact that a use is commercial as opposed to nonprofit is an additional element of the first fair use factor. The commercial nature of a use is relevant, but not dispositive. It is to be weighed against the degree to which the use has a further purpose or different character. Second, the first factor relates to the justification for the use. In a broad sense, a use that has a distinct purpose is justified because it furthers the goal of copyright, namely, to promote the progress of science and the arts, without diminishing the incentive to create. In a narrower sense, a use may be justified because copying is reasonably necessary to achieve the user’s new purpose. Parody, for example, “needs to mimic an original to make its point.” Id., at 580–581. Similarly, other commentary or criticism that targets an original work may have compelling reason to “conjure up” the original by borrowing from it. Id., at 588. An independent justification like this is particularly relevant to assessing fair use where an original work and copying use share the same or highly similar purposes, or where wide dissemination of a secondary work would otherwise run the risk of substitution for the original or licensed derivatives of it. See, e.g., Google, 593 U. S., at ___ (slip op., at 26).

In sum, if an original work and secondary use share the same or highly similar purposes, and the secondary use is commercial, the first fair use factor is likely to weigh against fair use, absent some other justification for copying. Pp. 13–20.

(2) The fair use provision, and the first factor in particular, requires an analysis of the specific “use” of a copyrighted work that is alleged to be “an infringement.” §107. The same copying may be fair when used for one purpose but not another. See Campbell, 510 U. S., at 585. Here, Goldsmith’s copyrighted photograph has been used in multiple ways. The Court limits its analysis to the specific use alleged to be infringing in this case—AWF’s commercial licensing of Orange Prince to Condé Nast—and expresses no opinion as to the creation, display, or sale of the original Prince Series works. In the context of Condé Nast’s special edition magazine commemorating Prince, the purpose of the Orange Prince image is substantially the same as that of Goldsmith’s original photograph. Both are portraits of Prince used in magazines to illustrate stories about Prince. The use also is of a commercial nature. Taken together, these two elements counsel against fair use here. Although a use’s transformativeness may outweigh its commercial character, in this case both point in the same direction. That does not mean that all of Warhol’s derivative works, nor all uses of them, give rise to the same fair use analysis. Pp. 20–27.

(b) AWF contends that the purpose and character of its use of Goldsmith’s photograph weighs in favor of fair use because Warhol’s silkscreen image of the photograph has a different meaning or message. By adding new expression to the photograph, AWF says, Warhol made transformative use of it. Campbell did describe a transformative use as one that “alter[s] the first [work] with new expression, meaning, or message.” 510 U. S., at 579. But Campbell cannot be read to mean that §107(1) weighs in favor of any use that adds new expression, meaning, or message. Otherwise, “transformative use” would swallow the copyright owner’s exclusive right to prepare derivative works, as many derivative works that “recast, transfor[m] or adap[t]” the original, §101, add new expression of some kind. The meaning of a secondary work, as reasonably can be perceived, should be considered to the extent necessary to determine whether the purpose of the use is distinct from the original. For example, the Court in Campbell considered the messages of 2 Live Crew’s song to determine whether the song had a parodic purpose. But fair use is an objective inquiry into what a user does with an original work, not an inquiry into the subjective intent of the user, or into the meaning or impression that an art critic or judge draws from a work.

Even granting the District Court’s conclusion that Orange Prince reasonably can be perceived to portray Prince as iconic, whereas Goldsmith’s portrayal is photorealistic, that difference must be evaluated in the context of the specific use at issue. The purpose of AWF’s recent commercial licensing of Orange Prince was to illustrate a magazine about Prince with a portrait of Prince. Although the purpose could be more specifically described as illustrating a magazine about Prince with a portrait of Prince, one that portrays Prince somewhat differently from Goldsmith’s photograph (yet has no critical bearing on her photograph), that degree of difference is not enough for the first factor to favor AWF, given the specific context and commercial nature of the use. To hold otherwise might authorize a range of commercial copying of photographs to be used for purposes that are substantially the same as those of the originals.

AWF asserts another related purpose of Orange Prince, which is to comment on the “dehumanizing nature” and “effects” of celebrity. No doubt, many of Warhol’s works, and particularly his uses of repeated images, can be perceived as depicting celebrities as commodities. But even if such commentary is perceptible on the cover of Condé Nast’s tribute to “Prince Rogers Nelson, 1958–2016,” on the occasion of the man’s death, the asserted commentary is at Campbell’s lowest ebb: It “has no critical bearing on” Goldsmith’s photograph, thus the commentary’s “claim to fairness in borrowing from” her work “diminishes accordingly (if it does not vanish).” Campbell, 510 U. S., at 580. The commercial nature of the use, on the other hand, “loom[s] larger.” Ibid. Like satire that does not target an original work, AWF’s asserted commentary “can stand on its own two feet and so requires justification for the very act of borrowing.” Id., at 581. Moreover, because AWF’s copy-ing of Goldsmith’s photograph was for a commercial use so similar to the photograph’s typical use, a particularly compelling justification is needed. Copying the photograph because doing so was merely helpful to convey a new meaning or message is not justification enough. Pp. 28–37.

(c) Goldsmith’s original works, like those of other photographers, are entitled to copyright protection, even against famous artists. Such protection includes the right to prepare derivative works that transform the original. The use of a copyrighted work may nevertheless be fair if, among other things, the use has a purpose and character that is sufficiently distinct from the original. In this case, however, Goldsmith’s photograph of Prince, and AWF’s copying use of the photograph in an image licensed to a special edition magazine devoted to Prince, share substantially the same commercial purpose. AWF has offered no other persuasive justification for its unauthorized use of the photograph. While the Court has cautioned that the four statutory fair use factors may not “be treated in isolation, one from another,” but instead all must be “weighed together, in light of the purposes of copy-right,” Campbell, 510 U. S., at 578, here AWF challenges only the Court of Appeals’ determinations on the first fair use factor, and the Court agrees the first factor favors Goldsmith. P. 38.

11 F. 4th 26, affirmed.

Sotomayor, J., delivered the opinion of the Court, in which Thomas, Alito, Gorsuch, Kavanaugh, Barrett, and Jackson, JJ., joined. Gorsuch, J., filed a concurring opinion, in which Jackson, J., joined. Kagan, J., filed a dissenting opinion, in which Roberts, C. J., joined.

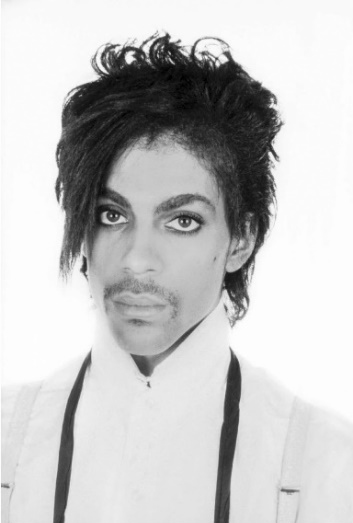

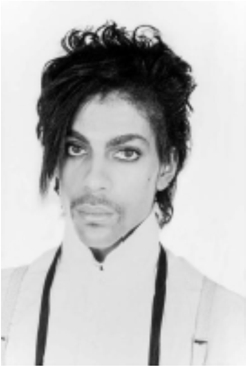

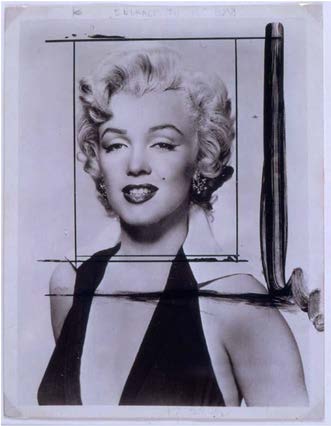

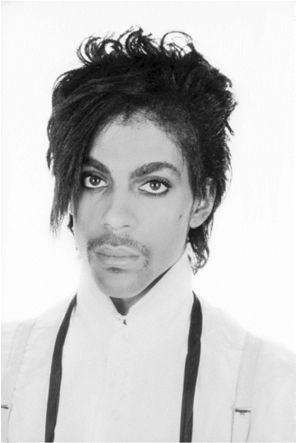

ANDY WARHOL FOUNDATION FOR THE VISUAL ARTS, INC., PETITIONER v. LYNN GOLDSMITH, et al. on writ of certiorari to the united states court of appeals for the second circuit [May 18, 2023] Justice Sotomayor delivered the opinion of the Court. This copyright case involves not one, but two artists. The first, Andy Warhol, is well known. His images of products like Campbell's soup cans and of celebrities like Marilyn Monroe appear in museums around the world. Warhol's contribution to contemporary art is undeniable. The second, Lynn Goldsmith, is less well known. But she too was a trailblazer. Goldsmith began a career in rock-and-roll photography when there were few women in the genre. Her award-winning concert and portrait images, however, shot to the top. Goldsmith's work appeared in Life, Time, Rolling Stone, and People magazines, not to mention the National Portrait Gallery and the Museum of Modern Art. She captured some of the 20th century's greatest rock stars: Bob Dylan, Mick Jagger, Patti Smith, Bruce Springsteen, and, as relevant here, Prince. In 1984, Vanity Fair sought to license one of Goldsmith's Prince photographs for use as an "artist reference." The magazine wanted the photograph to help illustrate a story about the musician. Goldsmith agreed, on the condition that the use of her photo be for "one time" only. 1 App. 85. The artist Vanity Fair hired was Andy Warhol. Warhol made a silkscreen using Goldsmith's photo, and Vanity Fair published the resulting image alongside an article about Prince. The magazine credited Goldsmith for the "source photograph," and it paid her $400. 2 id., at 323, 325-326. Warhol, however, did not stop there. From Goldsmith's photograph, he derived 15 additional works. Later, the Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. (AWF) licensed one of those works to Condé Nast, again for the purpose of illustrating a magazine story about Prince. AWF came away with $10,000. Goldsmith received nothing. When Goldsmith informed AWF that she believed its use of her photograph infringed her copyright, AWF sued her. The District Court granted summary judgment for AWF on its assertion of "fair use," 17 U. S. C. §107, but the Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit reversed. In this Court, the sole question presented is whether the first fair use factor, "the purpose and character of the use, including whether such use is of a commercial nature or is for nonprofit educational purposes," §107(1), weighs in favor of AWF's recent commercial licensing to Condé Nast. On that narrow issue, and limited to the challenged use, the Court agrees with the Second Circuit: The first factor favors Goldsmith, not AWF. I Lynn Goldsmith is a professional photographer. Her specialty is concert and portrait photography of musicians. At age 16, Goldsmith got one of her first shots: an image of the Beatles' "trendy boots" before the band performed live on The Ed Sullivan Show. S. Michel, Rock Portraits, N. Y. Times, Dec. 2, 2007, p. G64. Within 10 years, Goldsmith had photographed everyone from Led Zeppelin to James Brown (the latter in concert in Kinshasa, no less). At that time, Goldsmith "had few female peers." Ibid. But she was a self-starter. She quickly became "a leading rock photographer" in an era "when women on the scene were largely dismissed as groupies." Ibid. In 1981, Goldsmith convinced Newsweek magazine to hire her to photograph Prince Rogers Nelson, then an "up and coming" and "hot young musician." 2 App. 315. Newsweek agreed, and Goldsmith took photos of Prince in concert at the Palladium in New York City and in her studio on West 36th Street. Newsweek ran one of the concert photos, together with an article titled " 'The Naughty Prince of Rock.' " Id., at 320. Goldsmith retained the other photos. She holds copyright in all of them. One of Goldsmith's studio photographs, a black and white portrait of Prince, is the original copyrighted work at issue in this case. See fig. 1, infra.

Figure 1. A black and white portrait photograph of Prince taken in 1981 by Lynn Goldsmith.

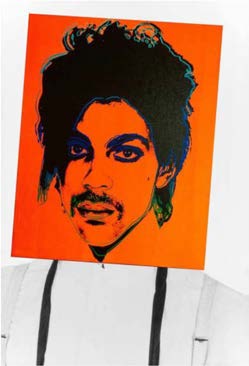

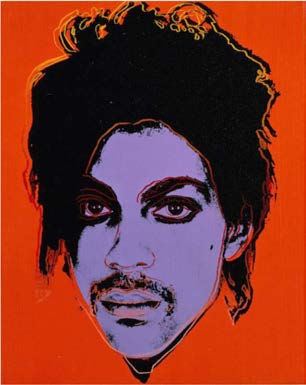

Figure 2. A purple silkscreen portrait of Prince created in 1984 by Andy Warhol to illustrate an article in Vanity Fair.

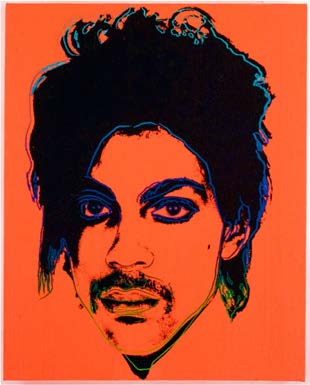

Figure 3. An orange silkscreen portrait of Prince on the cover of a special edition magazine published in 2016 by Condé Nast.

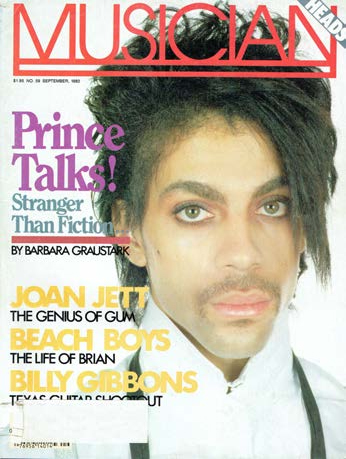

Figure 4. One of Lynn Goldsmith's photographs of Prince on the cover of Musician magazine.

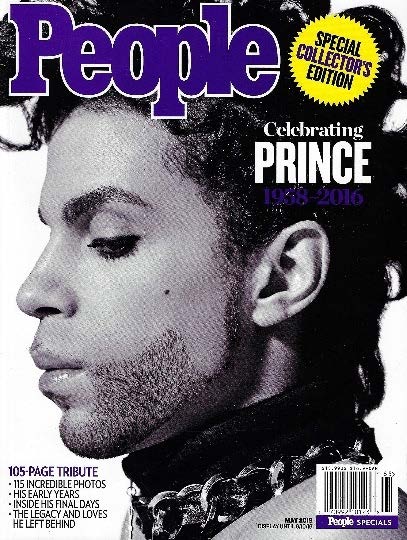

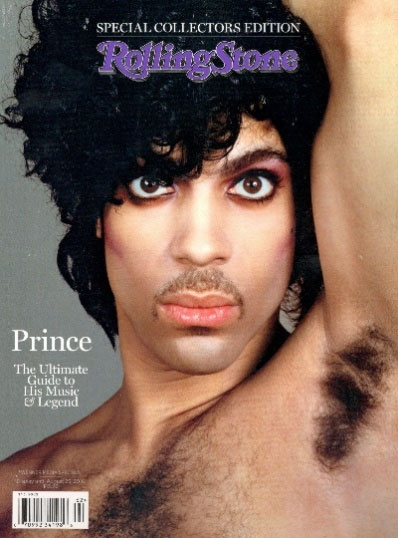

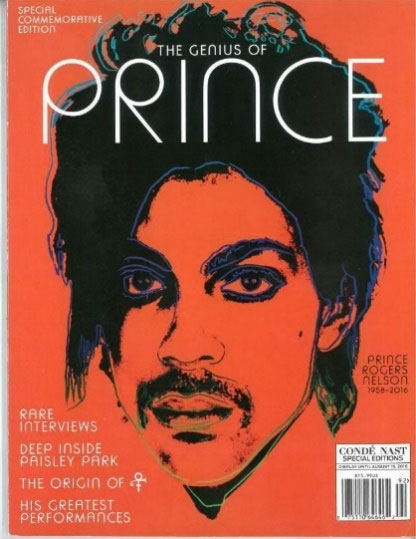

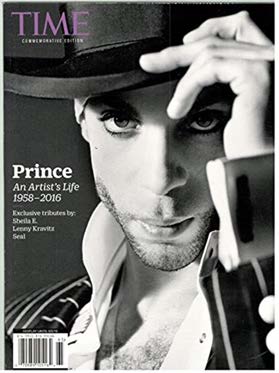

Figure 5. Four special edition magazines commemorating Prince after he died in 2016.

Figure 6. Warhol's orange silkscreen portrait of Prince superimposed on Goldsmith's portrait photograph.

Figure 7. A print based on the Campbell's soup can, one of Warhol's works that replicates a copyrighted advertising logo.

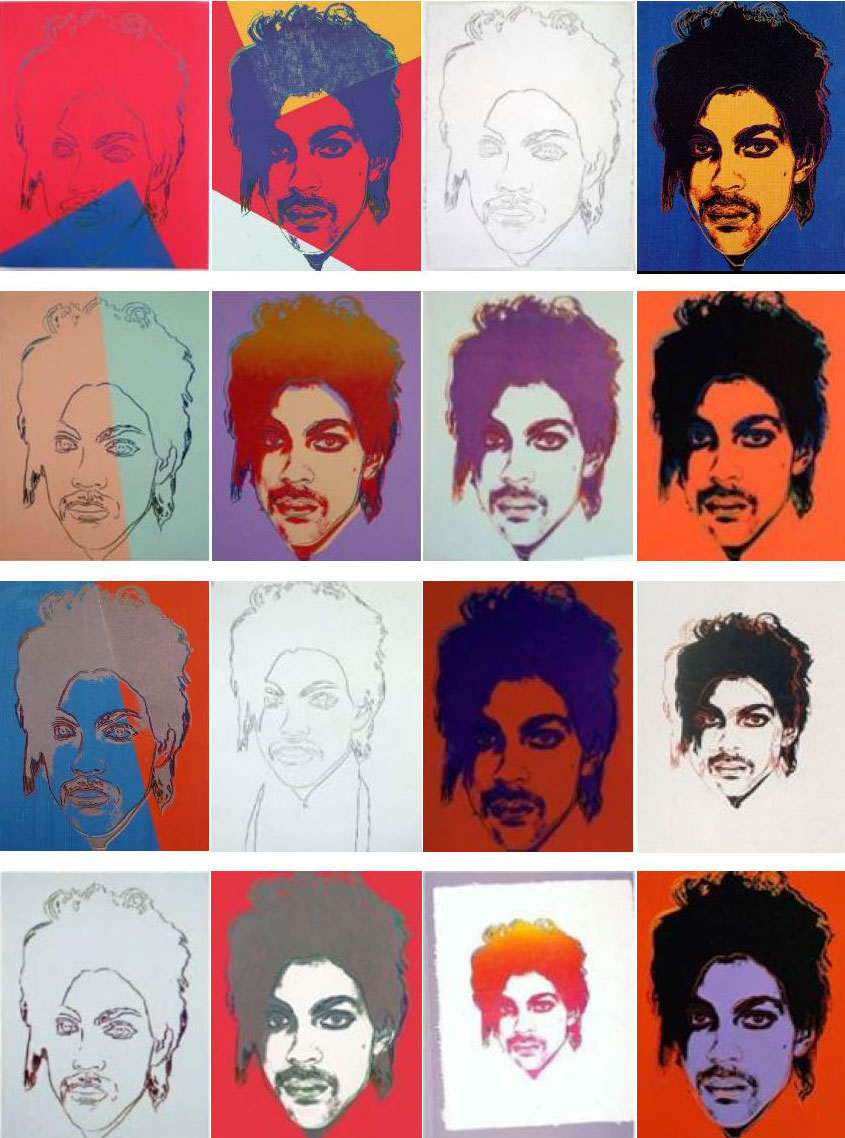

Andy Warhol created 16 works based on Lynn Goldsmith's photograph:14 silkscreen prints and two pencil drawings. The works are collectively known as the Prince Series.

Andy Warhol, Marilyn, 1964, acrylic and silkscreen ink on linen

Andy Warhol, Prince, 1984, synthetic paint and silkscreen ink on canvas

Giorgione, Sleeping Venus, c. 1510, oil on canvas

Titian, Venus of Urbino, 1538, oil on canvas

Manet, Olympia, 1863, oil on canvas

Velázquez, Pope Innocent X,c. 1650, oil on canvas

Francis Bacon, Study After Velazquez's Portrait of PopeInnocent X, 1953, oil on canvas

| Argued. For petitioner: Roman Martinez, Washington, D. C. For respondents: Lisa S. Blatt, Washington, D. C.; and Yaira Dubin, Assistant to the Solicitor General, Department of Justice, Washington, D. C. (for United States, as amicus curiae.) |

| Motion of the Solicitor General for leave to participate in oral argument as amicus curiae, for divided argument, and for enlargement of time for oral argument GRANTED. |

| Reply of The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. submitted. |

| Reply of petitioner The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. filed. (Distributed) |

| Amicus brief of Prof. Zvi S. Rosen submitted. |

| Amicus brief of Professor Terry Kogan submitted. |

| Amicus brief of Professor Guy A. Rub submitted. |

| Amicus brief of American Society of Media Photographers, Inc. submitted. |

| Amicus brief of United States submitted. |

| Amicus brief of California Society of Entertainment Lawyers; National Society of Entertainment & Art Lawyers; Bob Gomel; Dana Ruth Lixenberg; Bob Gruen submitted. |

| Motion of United States for leave to participate in oral argument and for divided argument submitted. |

| Motion of United States for leave to participate in oral argument and for divided argument submitted. |

| Amicus brief of Senator Marsha Blackburn submitted. |

| Amicus brief of Institute for Intellectual Property and Social Justice and Intellectual-Property Professors submitted. |

| Amicus brief of Digital Media Licensing Association submitted. |

| Amicus brief of Photographers Gary Bernstein and Julie Dermansky submitted. |

| Amicus brief of Association of American Publishers submitted. |

| Amicus brief of Jeffrey Sedlik submitted. |

| Amicus brief of Screen Actors Guild-American Federation of Television and Radio Artists submitted. |

| Amicus brief of Committee for Justice submitted. |

| Motion of the Solicitor General for leave to participate in oral argument as amicus curiae, for divided argument, and for enlargement of time for oral argument filed. |

| Amicus brief of Dr. Seuss Enterprises, L.P. submitted. |

| Amicus brief of Phoenix Center for Advanced Legal & Economic Public Policy Studies submitted. |

| Amicus brief of The Recording Industry Association of America and The National Music Publishers Association submitted. |

| Brief amici curiae of Photographers Gary Bernstein and Julie Dermansky filed. (Distributed) |

| Brief amicus curiae of Professor Terry Kogan filed. (Distributed) |

| Brief amicus curiae of Association of American Publishers filed. (Distributed) |

| Brief amici curiae of California Society of Entertainment Lawyers, et al. filed. (Distributed) |

| Brief amicus curiae of Committee for Justice filed. (Distributed) |

| Brief amici curiae of California Society of Entertainment Lawyers; National Society of Entertainment & Art Lawyers; Bob Gomel; Dana Ruth Lixenberg; Bob Gruen filed. (Distributed) |

| Brief amicus curiae of United States filed. (Distributed) |

| Brief amicus curiae of Phoenix Center for Advanced Legal & Economic Public Policy Studies filed. (Distributed) |

| Brief amici curiae of The Recording Industry Association of America and The National Music Publishers Association filed. (Distributed) |

| Brief amicus curiae of Screen Actors Guild-American Federation of Television and Radio Artists filed. (Distributed) |

| Brief amicus curiae of Senator Marsha Blackburn filed. (Distributed) |

| Brief amici curiae of American Society of Media Photographers, Inc., et al. filed. (Distributed) |

| Brief amicus curiae of Jeffrey Sedlik, Professional, Photographer and Photography Licensing Expert filed. (Distributed) |

| Brief amicus curiae of Digital Media Licensing Association filed. (Distributed) |

| Brief amicus curiae of Prof. Zvi S. Rosen filed. (Distributed) |

| Brief amicus curiae of Professor Guy A. Rub filed. (Distributed) |

| Brief amicus curiae of Photographers Gary Bernstein and Julie Dermansky filed. (Distributed) |

| Brief amici curiae of Institute for Intellectual Property and Social Justice and Intellectual-Property Professors filed. (Distributed) |

| Brief amicus curiae of Dr. Seuss Enterprises, L.P. filed. (Distributed) |

| Amicus brief of Graphic Artists Guild, Inc. and American Society for Collective Rights Licensing, Inc. submitted. |

| Amicus brief of Philippa S. Loengard submitted. |

| Brief amici curiae of Graphic Artists Guild, Inc. and American Society for Collective Rights Licensing, Inc. filed. (Distributed) |

| Brief amicus curiae of Philippa S. Loengard filed. (Distributed) |

| Amicus brief of Professors Peter S. Menell, Shyamkrishna Balganesh, and Jane C. Ginsburg as Amici Curiae in Support of Respondents submitted. |

| Brief amici curiae of Professors Peter S. Menell, Shyamkrishna Balganesh, and Jane C. Ginsburg as Amici Curiae in Support of Respondents filed. (Distributed) |

| Brief of Lynn Goldsmith, et al. submitted. |

| Brief of respondents Lynn Goldsmith, et al. filed. (Distributed) |

| CIRCULATED |

| The record from the U.S.C.A. 2nd Circuit has been electronically filed. |

| Record requested from the 2nd Circuit. |

| Amicus brief of Copyright Law Professors submitted. |

| Amicus brief of Barbara Kruger and Robert Storr submitted. |

| Amicus brief of Floor64, Inc. d/b/a The Copia Institute submitted. |

| Amicus brief of Art Professor Richard Meyer submitted. |

| Amicus brief of The Robert Rauschenberg Foundation, Roy Lichtenstein Foundation, and Brooklyn Museum submitted. |

| Amicus brief of Copyright Alliance submitted. |

| Amicus brief of Documentary Filmmakers submitted. |

| Amicus brief of Authors Guild, Inc., News Media Alliance, Sesame Workshop, Inc., Dramatists Legal Defense Fund, Romance Writers of America, Sisters in Crime, and Garden Communicators International submitted. |

| Amicus brief of Art Institute of Chicago, J. Paul Getty Trust, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Museum of Modern Art, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, Whitney Museum of American Art, and Association of Art Museum Directors submitted. |

| Amicus brief of Electronic Frontier Foundation and Organization For Transformative Works submitted. |

| Amicus brief of Library Futures Institute, The Software Preservation Network, The EveryLibrary Institute, The American Library Association, The Association of College and Research Libraries, and The Association of Research Libraries submitted. |

| Amicus brief of New York Intellectual Property Law Association submitted. |

| Brief amici curiae of Electronic Frontier Foundation, et al. filed. |

| Amicus brief of Authors Alliance submitted. |

| Amicus brief of American Intellectual Property Association submitted. |

| Amicus brief of The Motion Picture Association, Inc. submitted. |

| Brief amici curiae of The Robert Rauschenberg Foundation, et al. filed. |

| Brief amicus curiae of American Intellectual Property Association in suppoprt of neither party filed. |

| Brief amici curiae of Artists Barbara Kruger, et al. filed. |

| Brief amicus curiae of Art Professor Richard Meyer in support of neither party filed. |

| Brief amici curiae of Copyright Law Professors filed. |

| Brief amici curiae of Documentary Filmmakers filed. |

| Brief amicus curiae of Floor64, Inc. d/b/a The Copia Institute filed. |

| Brief amici curiae of Artists, et al. filed. |

| Brief amicus curiae of American Intellectual Property Law Association in suppoprt of neither party filed. |

| Brief amicus curiae of Copyright Alliance in support of neither party filed. |

| Brief amici curiae of Art Institute of Chicago, et al. in support of neither party filed. |

| Brief amicus curiae of The Motion Picture Association, Inc. in support of neither party filed. |

| Brief amicus curiae of New York Intellectual Property Law Association in support of neither party filed. |

| Brief amici curiae of Authors Guild, Inc., et al. in support of neither party filed. |

| Brief amici curiae of Library Futures Institute, et al. in support of neither party filed. |

| Brief amicus curiae of Authors Alliance filed. |

| Brief amicus curiae of Art Law Professors filed. |

| Amicus brief of Art Law Professors submitted. |

| Amicus brief of ROYAL MANTICORAN NAVY: THE OFFICIAL HONOR HARRINGTON FAN ASSOCIATION, INC. submitted. |

| Brief amicus curiae of Royal Manticoran Navy: The Official Honor Harrington Fan Association, Inc. filed. |

| ARGUMENT SET FOR Wednesday, October, 12, 2022. |

| Joint Appendix submitted. |

| Brief of The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. submitted. |

| Joint appendix (Volumes I and II) filed. (Statement of cost filed) |

| Brief of petitioner The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. filed. |

| Motion to extend the time to file the briefs on the merits granted. The time to file the joint appendix and petitioner's brief on the merits is extended to and including June 10, 2022. The time to file respondents' brief on the merits is extended to and including August 8, 2022. |

| Blanket Consent filed by Petitioner, The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. |

| Blanket Consent filed by Respondent, Lynn Goldsmith, et al. |

| Motion of The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. for an extension of time submitted. |

| Motion for an extension of time to file the briefs on the merits filed. |

| Petition GRANTED. |

| DISTRIBUTED for Conference of 3/25/2022. |

| DISTRIBUTED for Conference of 3/18/2022. |

| Reply of petitioner The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. filed. (Distributed) |

| Brief of respondents Lynn Goldsmith, et al. in opposition filed. |

| Brief amici curiae of Art Law Professors filed. |

| Brief amici curiae of The Robert Rauschenberg Foundation, Roy Lichtenstein Foundation, and Brooklyn Museum filed. |

| Brief amici curiae of Copyright Law Professors filed. |

| Brief amici curiae of Barbara Kruger and Robert Storr filed. |

| Motion to extend the time to file a response is granted and the time is extended to and including February 11, 2022. |

| Motion to extend the time to file a response from January 12, 2022 to February 11, 2022, submitted to The Clerk. |

| Petition for a writ of certiorari filed. (Response due January 12, 2022) |